Step into the forest. The air is thick with mist, the river glows with amber light, and a storm stirs above the pines. Somewhere, across the field, a lone painter captures it all with brush and oil. His name is Homer Watson.

The Boy Who Painted with Wind and Memory

Before he ever held a brush, Homer Watson wandered the rolling hills of Doon, Ontario: a boy marked by loss and wonder. His father died when he was six. A brother passed in a sudden accident, leaving Homer with a grief too large for words. So he walked. He watched the trees bend in the wind. He studied the way the river curled around the land like a question left unanswered.

By twelve, he was sketching in the margins of life, on fence posts, scraps of newspaper, and sometimes even in his porridge. His tools were few. His vision, vast.

Without formal schooling, he taught himself art by mimicking the masters from his father’s books. He’d copy Gustave Doré’s engravings and British landscapes with stubborn patience. Every tree he drew was one he had met. Every cloud, one he remembered.

A Stormy Sky Above the Queen’s Wall

In 1880, Watson painted The Pioneer Mill. It was more than a pastoral scene. It was a hymn to the old, creaking heartbeat of the Canadian wild. Lord Lorne, Canada’s Governor General, saw it and bought it on the spot… for Queen Victoria. Suddenly, Watson’s art hung not just in Doon but at Windsor Castle.

Oscar Wilde saw one of his works and called him “the Canadian Constable,” referencing the famed British landscape artist. But unlike Constable, Watson had never studied in Paris. He hadn’t wandered Barbizon or dined with patrons. He found his greatness in the woods behind his house. His Canada wasn’t a colony in his mind, it was a space to hold for love of nature.

The Land Was His Religion

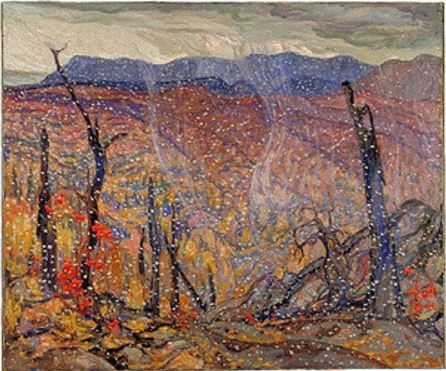

Watson wasn’t a preacher, but his reverence for nature was spiritual. He didn’t paint to copy what he saw, he painted to reveal what it meant. He believed that nature held stories. Secrets. Warnings. In his works, a farmhouse leaning into the wind might whisper of survival. A sunbeam breaking through thunderclouds might remind us that beauty, like hope, comes uninvited.

He spoke often of a mystical presence in the wild, like a kind of quiet divinity. He dabbled in spiritualism, yes, but his truest medium was paint. Where others saw trees, he saw memory. Where others saw farmland, he saw the bones of a country still dreaming itself into being.

The Weather Turned

As the 20th century marched on, new voices rose in the Canadian art world. The Group of Seven painted in bright, modern strokes. Watson, now older and nearly deaf, stood politely at the edge. He still painted. Still walked the woods. But galleries moved on. So did patrons.

The Great Depression hit hard. His savings vanished. His paintings – once royal gifts – sat unsold. He mortgaged his house. And yet, he never stopped. His last works, full of violet skies and thick brushstrokes, felt more dream than document. A world dissolving, or maybe reassembling, under his hand.

He died in 1936, in the same house he had filled with canvases and quiet wonder. The river outside still moved, the wind still danced in the trees. The paintings, silent, remained.

A House Full of Light

Today, that house still stands — not just as wood and stone, but as a living gallery. The Homer Watson House & Gallery in Kitchener preserves more than art. It preserves a way of seeing.

Inside, you’ll find Watson’s works alongside those of artists he inspired. You’ll walk the same halls where he welcomed guests, painted through the winter, and hung canvases like stained glass to nature’s memory. You can trace his brushstrokes, read his journals, and stand at the very window where the landscape outside once became myth inside his mind.

More than a museum, it’s a sanctuary for art, for Canada’s story, and for those who still believe a single brush can capture the pulse of a nation.

Visit Now! https://homerwatson.on.ca/

Leave a comment